Why Older Adults React Differently to Medications

Think about your favorite painkiller or blood pressure pill. Now imagine taking the same dose at 75 that you took at 45. For many older adults, that’s not just a small change-it’s a dangerous one. As we age, our liver and kidneys don’t work the same way they used to. These changes don’t show up on a routine blood test, but they can turn a safe medication into a serious risk. In fact, about 1 in 10 hospital stays for people over 65 are caused by bad reactions to medicines they were taking as prescribed.

What Happens to the Liver as We Age

The liver is the body’s main drug processor. It breaks down medicines so they can be cleared from the body. But after age 65, liver blood flow drops by about 40%. Liver mass shrinks by roughly 30%. These aren’t minor tweaks-they change how drugs move through the system.

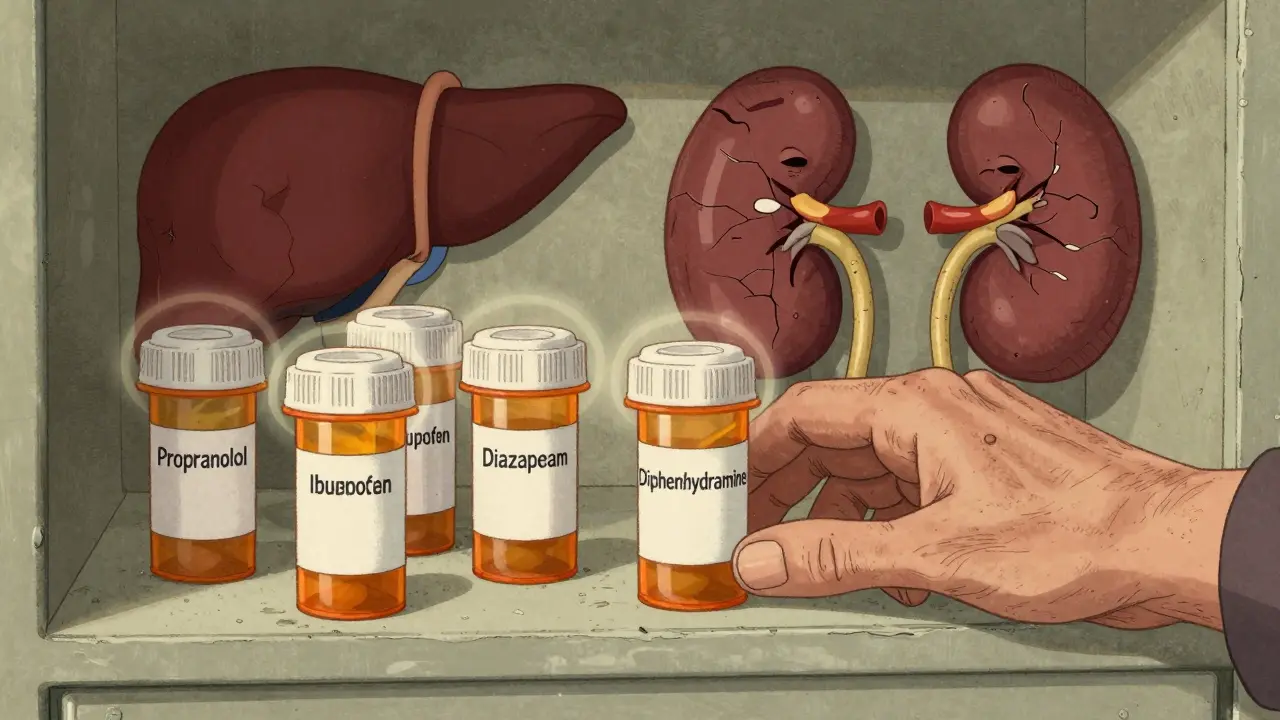

Some drugs rely on fast blood flow to be cleared. These are called flow-limited drugs. Examples include propranolol (for heart rhythm), lidocaine (a local anesthetic), and morphine (for pain). When liver blood flow drops, these drugs stick around longer. Their clearance can fall by up to 40%. That means even a normal dose can build up to toxic levels.

Other drugs, called capacity-limited drugs, depend more on enzyme activity than blood flow. These include diazepam (Valium), phenytoin (for seizures), and theophylline (for asthma). Their metabolism slows only a little-maybe 10-15%-because the enzymes that break them down don’t decline as sharply. But here’s the catch: if someone has both liver and kidney problems, even these drugs can become risky.

One overlooked issue is first-pass metabolism. Some drugs, like propranolol and verapamil, get broken down by the liver before they even enter the bloodstream. As liver function declines, more of the drug gets through. Bioavailability can jump by 25-50%. That means a 10 mg pill might act like a 15 mg pill. No one told you that. No label says it. But it’s happening.

How the Kidneys Slow Down

Kidneys filter drugs out of the blood. Their filtering power, called glomerular filtration rate (GFR), drops by 30-50% between ages 30 and 80. That’s not just a number-it’s a real, measurable decline in how fast your body clears drugs like digoxin, metformin, and many antibiotics.

Here’s where things get tricky: doctors often rely on serum creatinine to judge kidney function. But creatinine levels stay normal in older adults even when kidneys are failing. Why? Because muscle mass drops with age, and creatinine comes from muscle. So a 78-year-old with 40% kidney function might still have a “normal” creatinine level. That’s why the Cockcroft-Gault equation and the newer CKD-EPI formula are better-they account for age, weight, and sex. But not all clinics use them.

Drugs that are cleared mostly by the kidneys need lower doses in older adults. But here’s the twist: if the liver is also struggling, those same drugs might not get broken down properly in the first place. That means they pile up even faster. It’s a double hit.

Prodrugs and Hidden Risks

Some medicines don’t work until the body turns them into something else. These are called prodrugs. Perindopril (an ACE inhibitor for blood pressure) is one. It needs the liver to activate it. In older adults, that activation slows down. So the drug doesn’t work as well-yet the patient keeps taking the same dose, thinking it’s not helping. The doctor might increase it, not realizing the body can’t process it properly.

On the flip side, drugs like acetaminophen (Tylenol) are dangerous in older adults not because they’re metabolized slower, but because the liver is more vulnerable. Acetaminophen is the top cause of acute liver failure in seniors. Why? Because older livers have less glutathione, the antioxidant that neutralizes its toxic byproduct. A daily 1,000 mg dose that’s fine for a 50-year-old can be a silent threat to a 75-year-old.

What Happens When You Take Five Medications

More than 4 in 10 adults over 65 take five or more prescription drugs. That’s called polypharmacy. And it’s not just about the number-it’s about how those drugs interact with a slowing liver and kidneys.

One common example: an older person takes amitriptyline (for nerve pain or depression) and ibuprofen (for arthritis). Amitriptyline is processed by the liver. Ibuprofen can reduce kidney blood flow. Together, they can cause dizziness, confusion, or even falls. One Reddit user shared how their 82-year-old mother started amitriptyline at the standard dose and ended up in the ER with severe dizziness. The dose was cut in half-and she improved within days.

Another hidden danger: over-the-counter meds. Antacids, sleep aids, cold medicines-all can interfere. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) is a classic. It’s cleared by the liver and kidneys, causes drowsiness, and increases fall risk. Yet it’s still sold as “sleep aid” with no age warnings.

How Doctors Adjust Doses (And Why They Often Don’t)

There are clear guidelines. The Beers Criteria® says to start with 20-40% lower doses for liver-metabolized drugs in people over 65. For those over 75, go even lower. The STOPP/START criteria help avoid bad prescriptions and suggest better ones. Studies show using these tools cuts adverse drug events by 22%.

But here’s the problem: most doctors don’t routinely check liver or kidney function before prescribing. Or they use outdated formulas. Or they assume “normal” lab values mean everything’s fine. A 2022 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that nearly half of seniors on high-risk medications had no recent kidney function test.

Even when labs are checked, the results aren’t always interpreted correctly. A creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL might look normal. But for a frail 80-year-old woman who weighs 110 pounds, that could mean her kidneys are working at 40% capacity. Dose adjustments should be based on that-not the number on the chart.

New Tools Are Helping-But Not Everywhere

In 2023, the FDA approved the first software designed specifically for older adults: GeroDose v2.1. It lets doctors plug in age, weight, liver enzymes, and kidney function to predict how a drug will behave in that person’s body. It’s not magic-but it’s better than guessing.

Researchers are also finding that epigenetics play a role. Some older adults have gene changes that make their liver enzymes work faster or slower than expected. That’s why two people the same age can react completely differently to the same drug.

But these tools aren’t in every clinic. Most still rely on age-based rules or outdated formulas. And drug trials? Only 38% of participants in new drug studies are over 65. That means we’re prescribing medicines based on data from people decades younger.

What You Can Do

If you or a loved one is over 65 and taking multiple medications:

- Ask your doctor: “Is this dose right for my liver and kidneys-not just my age?”

- Request a kidney function test using the CKD-EPI formula (not just creatinine).

- Review all meds-prescription, OTC, and supplements-at least once a year.

- Never start a new OTC drug without checking with your pharmacist. Even “harmless” sleep aids can be risky.

- If you feel dizzy, confused, or unusually tired after starting a new drug, speak up. It might not be “just aging.”

There’s no reason for older adults to suffer from preventable drug reactions. The science is clear. The tools exist. What’s missing is consistent application. Your body changes with age. Your meds should too.

Do all older adults process drugs the same way?

No. While liver and kidney function generally decline with age, the rate varies widely. One 75-year-old might have kidney function close to a 50-year-old, while another has severe impairment. Genetics, chronic illness, muscle mass, and even diet affect how drugs are processed. That’s why using age alone to adjust doses isn’t enough-you need to look at actual organ function.

Can I just take half the dose if I’m older?

Not always. Some drugs need a smaller reduction-others need a bigger one. For example, a blood thinner like warfarin might need a 30% reduction, while a sleep aid like zolpidem might need a 50% cut. Some drugs, like insulin or digoxin, require blood level monitoring, not just dose guesses. Never adjust your dose without talking to your doctor or pharmacist.

Why do some seniors react badly to drugs that worked fine when they were younger?

Because their bodies don’t clear drugs the same way anymore. The liver processes them slower, the kidneys filter them out less efficiently, and their brain becomes more sensitive to side effects like dizziness or confusion. A drug that was safe at 50 can become dangerous at 75-not because it changed, but because their body changed.

Are herbal supplements safe for older adults?

Many aren’t. St. John’s Wort can interfere with blood thinners and antidepressants. Ginseng can affect blood sugar and blood pressure. Turmeric can increase bleeding risk. These supplements are processed by the liver and kidneys-just like prescription drugs. Just because they’re “natural” doesn’t mean they’re safe, especially with age-related changes.

How often should kidney and liver function be checked in seniors?

At least once a year for anyone over 65 on regular medications. If you’re on kidney- or liver-sensitive drugs (like diuretics, statins, or antidepressants), check every 3-6 months. If your health changes-like losing weight, getting sick, or starting a new drug-get tested right away. Don’t wait for your next routine visit.

What’s Next for Senior Medication Safety

The future is moving toward personalized dosing-not based on age, but on actual biology. Blood tests for liver enzymes, kidney markers, and even genetic markers are becoming more accessible. In the next five years, we’ll likely see more clinics using digital tools like GeroDose to guide prescriptions.

But the biggest change needs to happen in how we think. Aging isn’t a disease. But treating older adults like younger people with wrinkles is dangerous. Medication safety for seniors isn’t about being cautious-it’s about being precise. And that precision starts with understanding how the liver and kidneys really change as we grow older.

Kelly Weinhold

January 31, 2026 AT 04:56Wow, this post hit me right in the feels. My mom’s on like six meds and I swear she’s been walking like a drunk penguin since they added that new sleep aid. No one ever told us Benadryl was a landmine for seniors. We just thought she was getting ‘old.’ Now I’m going through every pill bottle with her this weekend-OTC, supplements, everything. If we can prevent one ER trip, it’s worth it. Thanks for laying it out so clearly.

Sidhanth SY

January 31, 2026 AT 13:59As someone who’s seen this play out in rural India too-same story. Grandmas on 5 pills, no one checks kidney function, and the local doctor just says ‘take half.’ But half of what? No one knows. The real issue? No one talks about it. We fix the fever, not the system. I wish more docs here used CKD-EPI. Most still use creatinine like it’s 1998. It’s not laziness-it’s ignorance wrapped in tradition.

Katie and Nathan Milburn

January 31, 2026 AT 18:04It is of considerable importance to underscore the systemic deficiencies in geriatric pharmacological management, particularly in light of the documented decline in hepatic perfusion and glomerular filtration rate associated with advanced age. The reliance upon serum creatinine as a sole biomarker for renal function is not only outdated but also clinically indefensible in the context of sarcopenia. The application of the CKD-EPI equation, while statistically superior, remains underutilized due to institutional inertia and lack of standardized protocols. Further, the paucity of geriatric representation in clinical trials constitutes a profound epistemological gap in evidence-based medicine.

Beth Beltway

January 31, 2026 AT 18:27Of course this is happening. People are just too lazy to think. You don’t get to be 75 and still take the same dose as a 30-year-old and then act surprised when you feel like crap. It’s not rocket science. If your liver’s slow, your kidneys are slow, and you’re on five drugs-you’re basically a walking toxic waste experiment. And don’t even get me started on people popping St. John’s Wort like candy. ‘Natural’ doesn’t mean ‘safe.’ It means ‘unregulated and possibly lethal.’ Someone needs to start enforcing accountability, not just handing out pamphlets.

kate jones

February 1, 2026 AT 08:44Let’s clarify a few key pharmacokinetic principles here. First-pass metabolism reduction in aging livers directly elevates bioavailability of high-extraction drugs like propranolol-this is well-documented in clinical pharmacology literature (e.g., Rowland & Tozer, 2011). Concurrently, age-related decline in GFR necessitates dose adjustments for renally cleared agents, particularly those with narrow therapeutic indices (e.g., digoxin, vancomycin). The Cockcroft-Gault equation remains clinically relevant for dosing, despite CKD-EPI’s superior population-level accuracy, because it incorporates weight-a critical variable in frail elderly. Additionally, polypharmacy interactions are not merely additive; they are synergistic, often mediated by CYP450 inhibition (e.g., amitriptyline + NSAIDs → reduced renal perfusion + anticholinergic burden). The FDA’s GeroDose tool is a step forward, but its adoption requires EHR integration and clinician education. Until then, pharmacist-led medication reviews remain the most effective intervention.

Diksha Srivastava

February 2, 2026 AT 09:15This is so true. My aunt took Tylenol every day for her back pain-1000mg, like it was candy. She ended up in the hospital with liver failure. No one told her older liver = less glutathione = more damage. She’s fine now, but it scared the heck out of us. I started printing out simple charts for my family: ‘What to avoid after 65.’ We’re not doctors, but we can be smart. Just because something’s on the shelf doesn’t mean it’s safe for us. Small changes save lives.

Jason Xin

February 3, 2026 AT 14:10So let me get this straight. We have AI tools that can predict how a drug behaves in a 78-year-old’s body… but most doctors still eyeball doses based on ‘age 65+ = half the pill’? And the FDA approved a tool called GeroDose, but it’s not in 90% of clinics? Meanwhile, my 80-year-old neighbor is still getting Benadryl for sleep. The system isn’t broken-it’s been designed this way. Profit over precision. Convenience over care. And we wonder why seniors are falling, hallucinating, or ending up in the ER.