Hypocalcemia Risk Assessment Calculator

How IBD Affects Your Calcium Risk

This calculator helps you understand your personal risk of developing hypocalcemia based on your IBD characteristics, medications, and lifestyle factors. Hypocalcemia can lead to bone loss, muscle cramps, and other serious complications if not addressed early.

Assess Your Risk

People living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) often hear about flare‑ups, diarrhea, and weight loss. What’s less talked about is how the condition can tip the body’s calcium balance into the low‑range, a state known as hypocalcemia. If you’ve been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, you might wonder why you feel bone‑pain, muscle cramps, or even tingling in your fingertips. The answer usually lies in a hidden connection between gut health and calcium metabolism.

Quick Takeaways

- Hypocalcemia is low blood calcium, often caused by malabsorption in IBD.

- Vitamin D deficiency, altered parathyroid hormone (PTH) response, and certain medications increase risk.

- Typical symptoms include muscle cramps, numbness, and bone‑density loss.

- Diagnosis relies on serum calcium, ionized calcium, and vitaminD testing.

- Management blends diet, supplements, medication review, and regular monitoring.

What Is Hypocalcemia?

Hypocalcemia is a condition where the concentration of calcium in the blood falls below the normal reference range (generally < 8.5mg/dL or < 2.12mmol/L). Calcium is essential for muscle contraction, nerve signaling, and bone strength, so a shortage sends warning signals throughout the body.

Two lab values matter most: total serum calcium (which includes calcium bound to proteins) and ionized calcium (the physiologically active form). In clinical practice, doctors often confirm low ionized calcium before labeling a patient as truly hypocalcemic.

What Is Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) groups together chronic disorders that cause inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. The two main types are Crohn’s disease, which can affect any part of the gut from mouth to anus, and Ulcerative colitis, which is limited to the colon and rectum.

IBD’s hallmark symptoms-diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue-are driven by an overactive immune response that damages the lining of the gut. Over time, repeated inflammation can impair nutrient absorption, alter hormone signaling, and even change how the kidneys handle electrolytes.

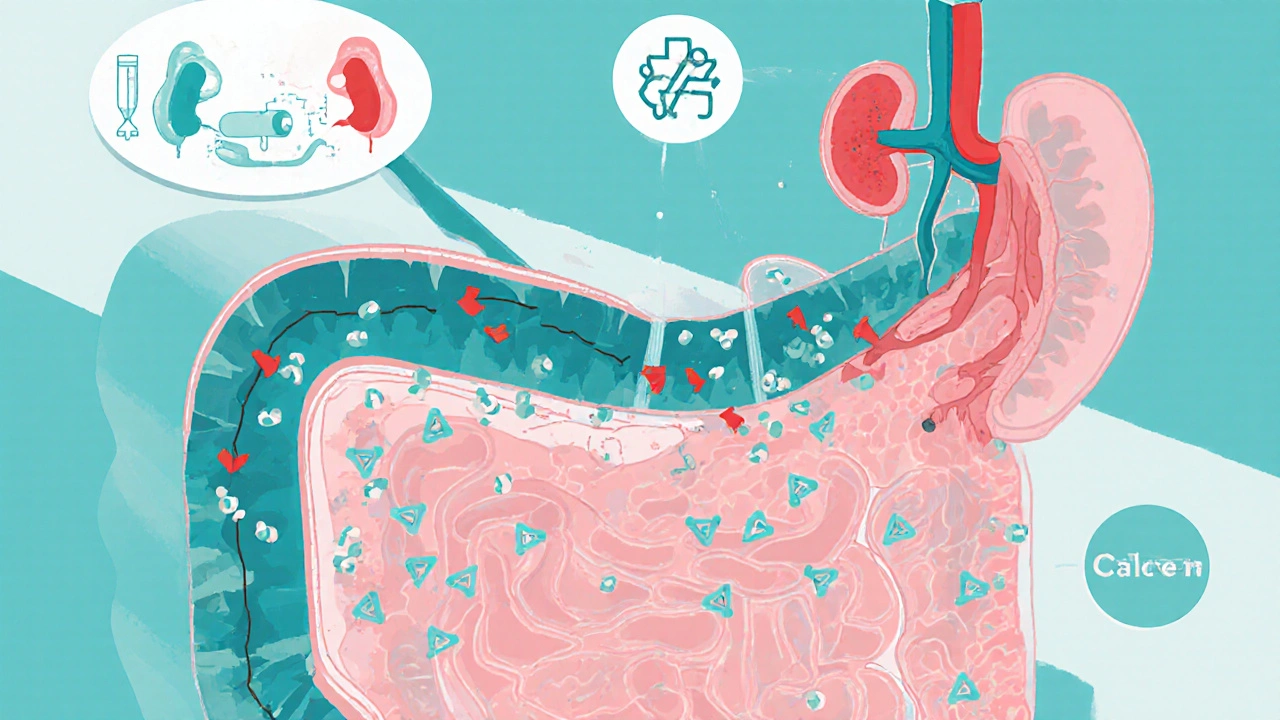

How Do the Two Conditions Connect?

The gut and calcium system talk to each other through several pathways:

- Malabsorption - Inflamed intestinal walls, especially in the duodenum and jejunum, struggle to absorb calcium and vitaminD from food.

- Vitamin D deficiency - IBD patients often have low sun exposure and reduced dietary intake, weakening the body’s ability to convert vitaminD into its active form (calcitriol), which is needed for calcium uptake.

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH) dysregulation - Chronic inflammation can blunt the parathyroid glands’ response, so when calcium drops, PTH doesn’t rise enough to pull calcium from bone or kidneys.

- Medication side effects - Steroids, biologics, and certain antibiotics used in IBD can increase calcium loss through the kidneys or gut.

All these factors create a perfect storm where blood calcium levels slip, often without obvious immediate symptoms.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Not every IBD patient will develop hypocalcemia, but some groups face higher odds:

- Patients with extensive small‑bowel disease or surgical resection of the duodenum.

- Those on long‑term corticosteroids or proton‑pump inhibitors.

- Individuals with low dietary calcium (<800mg/day) and insufficient vitaminD (<20ng/mL).

- Elderly patients, because age‑related bone loss amplifies the impact of low calcium.

Typical Symptoms to Watch For

Because calcium plays many roles, low levels can show up in different ways. Common red flags include:

- Muscle cramps or spasms, especially in calves.

- Tingling or “pins‑and‑needles” sensations around the mouth and fingertips.

- Sudden heart palpitations or irregular beats.

- Bone pain, fractures from minor trauma, or decreasing bone density on DEXA scans.

- Severe cases may cause seizures or a life‑threatening cardiac arrhythmia.

If any of these appear during an IBD flare, bring them up with your gastroenterologist right away.

How Is Hypocalcemia Diagnosed in IBD?

Diagnosis follows a step‑wise approach:

- Blood draw for total calcium, ionized calcium, albumin (to correct total calcium), and magnesium.

- Check vitaminD status (25‑hydroxy‑vitaminD) and intact PTH levels.

- Evaluate kidney function (creatinine, eGFR) because renal loss can mimic gut‑related hypocalcemia.

- When the cause isn’t obvious, imaging (e.g., DEXA for bone density) helps gauge long‑term impact.

Most labs will flag low calcium automatically; the challenge is linking it back to IBD‑related mechanisms.

Management Strategies

Treating hypocalcemia in IBD is a blend of fixing the deficiency and addressing the underlying gut issue.

1. Dietary Adjustments

Aim for 1,000-1,200mg of calcium a day (higher if you’re over 50). Sources that are easier on the gut include:

- Low‑lactose dairy (Greek yogurt, hard cheeses).

- Fortified plant milks (almond, soy) with added calcium and vitaminD.

- Leafy greens like kale and collard greens (lower oxalate than spinach).

- Small, frequent meals to reduce irritation during a flare.

2. VitaminD Supplementation

Most IBD guidelines recommend 1,000-2,000IU of vitaminD3 daily, adjusting upward if blood levels remain <30ng/mL. In severe deficiency, a loading dose of 50,000IU weekly for 8 weeks is common, followed by maintenance.

3. Calcium Supplements

If diet and vitaminD aren’t enough, calcium carbonate or calcium citrate can be added. Calcium citrate is better tolerated when stomach acid is low (e.g., on PPIs). Typical dosing: 500-600mg two to three times daily, taken with meals.

4. Review Medications

Talk to your doctor about steroid tapering, using the lowest effective dose, or switching to steroid‑sparing agents. Some biologics (like anti‑TNF agents) may actually improve calcium absorption by reducing gut inflammation.

5. Treat Underlying IBD Activity

Effective disease control reduces malabsorption. Options include:

- Biologic therapies (infliximab, ustekinumab) for moderate‑to‑severe disease.

- Small‑molecule drugs (tofacitinib) for ulcerative colitis.

- Nutritional therapies (exclusive enteral nutrition) especially in pediatric Crohn’s.

6. Monitor and Adjust

After starting supplements, re‑check calcium, ionized calcium, and vitaminD in 4-6 weeks. Adjust doses based on labs and symptoms. For patients with chronic bone loss, a yearly DEXA scan helps guide the need for bisphosphonates or other bone‑protective drugs.

Practical Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

- Ask for baseline calcium, ionized calcium, vitaminD, and PTH at every IBD visit.

- Document dietary calcium intake; consider a food‑frequency questionnaire.

- Review current medications for calcium‑depleting potential.

- Start calcium‑rich foods or supplements if intake <800mg/day.

- Prescribe vitaminD3 1,000IU daily; increase if labs show deficiency.

- Schedule labs again in 4-6 weeks after any change.

- Refer to a dietitian familiar with IBD for personalized meal planning.

- Order a DEXA scan if calcium remains low for >6 months or if there’s a fracture history.

Looking Ahead: Research Trends

Recent studies (2023‑2024) highlight that gut microbiota can influence calcium absorption by modulating vitaminD metabolism. Probiotic blends containing Lactobacillusrhamnosus are being tested as adjuncts to improve bone density in IBD patients. Keep an eye on clinical trial registries; the next wave of therapies may target the gut‑bone axis directly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get enough calcium from food alone?

Many people with IBD can meet their daily calcium needs through fortified dairy or plant milks, leafy greens, and low‑lactose cheeses. However, active disease often limits absorption, so most clinicians add a supplement once blood levels dip below normal.

Is calcium deficiency the same as vitaminD deficiency?

No. Calcium is the mineral that muscles and bones need; vitaminD is a hormone that tells the gut to absorb calcium. You can be low in one, the other, or both. Treating just one won’t fully correct the problem if the partner is also deficient.

Will stopping steroids fix my calcium levels?

Reducing steroids can help, because they increase calcium loss through the kidneys. However, you still need to address malabsorption and vitaminD status; a combined approach works best.

How often should I get my calcium checked?

If you’re on supplements, check labs every 3-4 months until stable, then twice a year. During a flare, more frequent testing (monthly) may be warranted.

Can low calcium cause my IBD symptoms to worsen?

Low calcium itself doesn’t trigger gut inflammation, but the muscle cramps and fatigue it causes can make flare‑management harder. Keeping calcium normal supports overall health and may improve quality of life.

Take Action Today

Start by asking your gastroenterologist for a calcium panel at your next appointment. Pair that with a quick food log to see where you stand on calcium and vitaminD intake. Small changes-adding a fortified cereal, swapping to calcium citrate, or stepping out for a short walk in the sun-can move the needle fast. And remember, keeping your gut calm is the best long‑term defense against calcium loss.

S O'Donnell

October 12, 2025 AT 00:17Calcium absorption primarily occurs in the duodenum and proximal jejunum, regions that are frequently inflamed in Crohn’s disease, which can dramatically reduce the efficiency of dietary calcium uptake.

When the mucosal surface is damaged, the expression of calcium transport proteins such as TRPV6 and calbindin‑D9k declines, leading to a net negative balance even if intake appears adequate.

The situation is compounded by vitamin D deficiency, a common finding in IBD patients due to limited sun exposure, malabsorption of fat‑soluble vitamins, and the use of corticosteroids that accelerate vitamin D catabolism.

Low circulating calcitriol then fails to up‑regulate intestinal calcium channels, creating a feedback loop that pushes serum calcium into the hypocalcemic range.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) normally compensates by increasing renal calcium reabsorption and stimulating bone resorption, but chronic inflammation can blunt the parathyroid response, a phenomenon sometimes called “secondary hyperparathyroidism failure.”

Furthermore, long‑term steroid therapy, which is a mainstay for many IBD flares, directly promotes calcium loss through enhanced urinary excretion and inhibition of osteoblast activity.

Proton‑pump inhibitors, another class frequently prescribed for gastro‑esophageal reflux in IBD, have been linked to reduced calcium absorption by raising gastric pH, thereby impairing solubilisation of calcium salts.

All these mechanisms converge to raise the risk of bone demineralisation, osteoporosis, and fractures, especially in younger patients who have not yet achieved peak bone mass.

From a diagnostic perspective, measuring both total serum calcium and ionized calcium is essential, because albumin fluctuations in chronic illness can mask true hypocalcemia.

Concurrent assessment of 25‑hydroxy‑vitamin D, PTH, and alkaline phosphatase helps differentiate between simple dietary deficiency and more complex endocrine dysregulation.

Management should begin with dietary optimisation: incorporate calcium‑rich foods such as fortified plant milks, leafy greens, and low‑oxalate nuts, while ensuring adequate vitamin D intake through sunlight or supplementation.

If oral supplementation is required, calcium carbonate is best taken with meals, whereas calcium citrate is preferable for patients with reduced gastric acidity.

Monitoring intervals of three to six months are advisable, with repeat labs to verify that serum calcium has stabilised and that PTH is no longer elevated.

Finally, consider involving a bone health specialist early, as bisphosphonates or denosumab may be indicated for patients with persistent low bone density despite correction of calcium and vitamin D levels.

Yamunanagar Hulchul

October 22, 2025 AT 18:57Wow! This info is a game‑changer for anyone wrestling with IBD and the dreaded calcium slump!!! 🌟 Keep the tips coming!!!

Sangeeta Birdi

November 2, 2025 AT 12:37Sending you a big hug ❤️! It’s tough dealing with cramps and tingling, but remember you’re not alone-many of us have walked this path and found relief with the right supplements and regular check‑ups 😊.

Chelsea Caterer

November 13, 2025 AT 07:17Calcium loss is a silent foe, so track those levels regularly.

Lauren Carlton

November 24, 2025 AT 01:57While the article covers the basics, it omits the impact of chronic diarrhea on bicarbonate loss, which indirectly affects calcium binding; also, the role of fibroblast growth factor‑23 in phosphate handling is worth a mention because it can further destabilise mineral balance.

Katelyn Johnson

December 4, 2025 AT 20:37Great summary and super helpful for folks looking for practical steps, love how inclusive it feels for everyone regardless of diet or background.

Elaine Curry

December 15, 2025 AT 15:17Interesting point about FGF‑23-most patients never get screened for that, but it can explain why some still have low calcium despite vitamin D repletion.

Patrick Fortunato

December 26, 2025 AT 09:57Totally agree, the enthusiasm helps keep morale up when the daily grind feels endless.

Manisha Deb Roy

January 6, 2026 AT 04:37Pro tip: try a chewable calcium citrate with vitamin D3 2000 IU after meals-it’s easier on the gut and many patients report less bloating compared to carbonate. Gonna make it a part of your routine and watch the difference.

Helen Crowe

January 16, 2026 AT 23:17Leverage this momentum by integrating a bone turnover marker panel; tracking serum CTX and P1NP can give realtime feedback on treatment efficacy and keep you ahead of the curve.